Justine Frank

(Born: Anwerp, 1900; died: Tel Aviv, 1943)

Anonymous photographer, Justine Frank, Paris, ca. 1928

The art of the fictive Jewish Belgian painter Justine Frank has long been neglected and suppressed. Her work joins erotic motifs and Jewish imagery—a disturbing, hallucinatory combination. The same mixture of smut and Jewish tropes appears in the only book she authored, the pornographic novel Sweet Sweat (1931).

As soon as Frank emigrated from Antwerp to Paris, she mingled with members the Surrealist movement. While the Surrealists advocated a radical investigation of sexuality, the place allotted women-artists in this enterprise was rather scarce, and the scatological nature of Frank’s imagery repelled them. The Jewish tropes in Frank’s paintings were an anomaly as well. While a sacrilegious assault on Catholicism was a staple of Surrealism, Jewish Surrealists abstained from addressing this facet of their identity in their art—and Frank’s spectacle of Judaism was far too baffling to be understood as merely satirical.

Anonymous photographer, Justine Frank, ca. 1933

Justine Frank and her friend Fanja Hissin on the seashore of Tel Aviv, 1936

Frank’s career was also hindered by her intimate relationship with controversial author Georges Bataille, who at that time was having a veritable war with Surrealist leader André Breton. Her personal, financial and professional difficulties, along with the ominous intensification of anti-Semitism in Europe finally brought the artist to emigrate to Palestine in 1934. She settled in Tel Aviv, hometown of her best friend, Fanja Hissin, a kiosk owner widowed a year earlier. Yet opting for Tel Aviv was odd, if not tragic. Frank had always disavowed nationalist ideologies; once in Tel Aviv, her attitude became one of manifested hostility towards the values of the Zionist society. She persisted with her disagreeable artistic amalgamation of erotica and Judaism in the context of a puritan culture, whose “melting pot” ideology called for the suppression and negation of the diasporic Jew Frank was so adamantly rendering.

Frank was living virtually as an untouchable. But the social banishment did not prevent an unremitting buzz of ill-willed gossip around her. Some of these rumors were patently false. But as the years went by and her condition deteriorated further, her behavior did indeed become more disconcerting. In 1940 she began to persistently pester Marcel Janco, the venerated artist and recent immigrant. For her, it seems, Janco was simultaneously an alter ego, a nemesis, and a traitor, exchanging the radical stance of the avant-garde for nationalist local patriotism.

On April 22nd, 1942, Frank arrived as an uninvited guest, at the opening of an exhibition entitled Desert Light and Light Unto the Nations. According to most accounts, Frank attempted to assault Janco, and was arrested. Whatever truly happened, the event had doubtlessly scarred Frank. After Fanja Hissin bailed her, she moved in with the widower. In the early afternoon hours of April 12th, 1943, Justine Frank left Hissin’s apartment. She was never seen again.

The Stained Portfolio

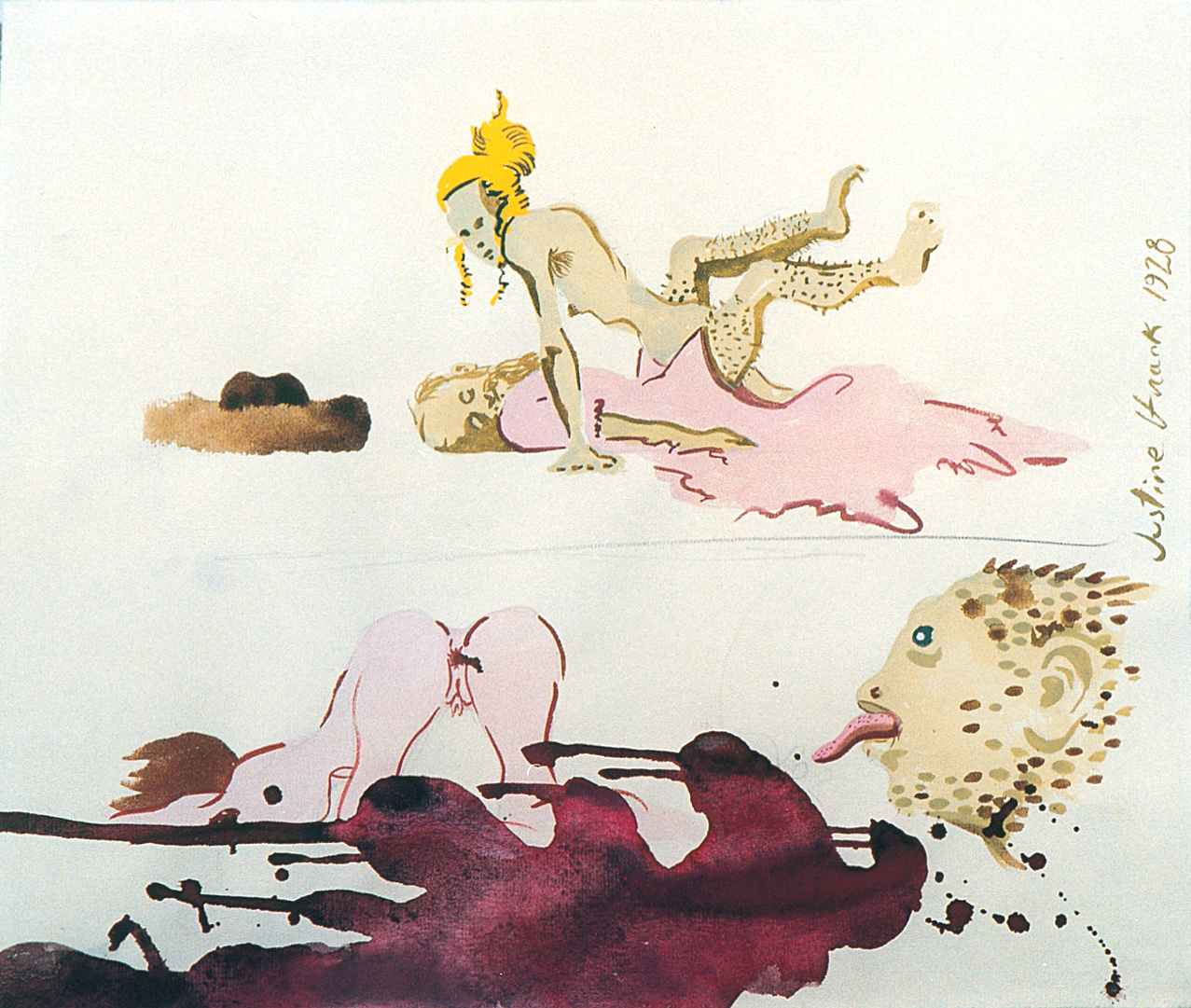

130 drawings and gouaches on paper, 1927-1928

This dossier of drawings—all stained (probably by ink)—is the earliest extant work by Frank. The assumption that the sheets were stained accidentally seems farfetched, as some of the blots clearly suggest figurations. Intentional staining also seems typical of Frank’s artistic antics: a bent for illusion and deceit, a scatological compulsion, and also a self destructive tendency, which might have found expression in the willful desecration of this exceptionally labor-intensive work.

But the stains are not the only anomalous trait of the portfolio. Unlike any known sketchbook in art history, the portfolio contains a preparatory study for each and every painting Frank was to produce later on. This fact, considered along with the early date, gave rise to two contradictory theories. According to the first, which perceives the dates as genuine, Frank planned her creative development in advance. The portfolio thus enables us to perceive Frank’s oeuvre (and, indeed, her life), as a single gesamtkunstwerk of monstrous scale. If so, Frank’s leitmotif is a parodic reversal of accepted notions concerning artistic inspiration and creation. This interpretation seems all the more stunning as Frank’s style did, in fact, evolve substantially over the years, and clear connections between biography and subject matter in her art can be easily traced.

Another possibility is that Frank backdated the drawings later, perhaps even in the 40’s (other artists, such as Malevich and de Chirico back-dated works, an act motivated either by a better market for early works, or by the will to retrospectively revise the artist’s history). Regardless of the answers to these questions, the comprehensive scope of the portfolio offers an excellent introduction to the work of Justine Frank, It providing a lexical key to her themes, symbols and tropes.

Frankomas, oil on canvas, 1930

Justine Frank, The Sisters Frankomas, oil on canvas, 1931

Justine Frank, Still Life, oil on canvas, 1934

Justine Frank, Utamaro and the Hysteric, gouache on paper, 1936

Justine Frank, Frank’s Guild, oil on canvas, 1936

Justine Frank, Untitled (Self Portrait as a Black Woman), oil on canvas, 1938

Installation shots, Roee Rosen, A Group Exhibition, The Tel Aviv Museum, 2016

Photographer: Revital Topol